Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn

Villa Comunale

80121 - Naples, Italy

Tel.: +39 081 5833111

Fax: +39 081 7641355

Secretariat: +39 081 5833218 - 307

e-mail: stazione.zoologica(at)szn.it

ufficio.protocollo(at)cert.szn.it

Ischia

"Villa Dohrn"

Punta S. Pietro

80077 - Ischia, Naples, Italy

Tel. +39 081 5833521

Fax. +39 081 984201

e-mail: rosanna.messina(at)szn.it

| Description |

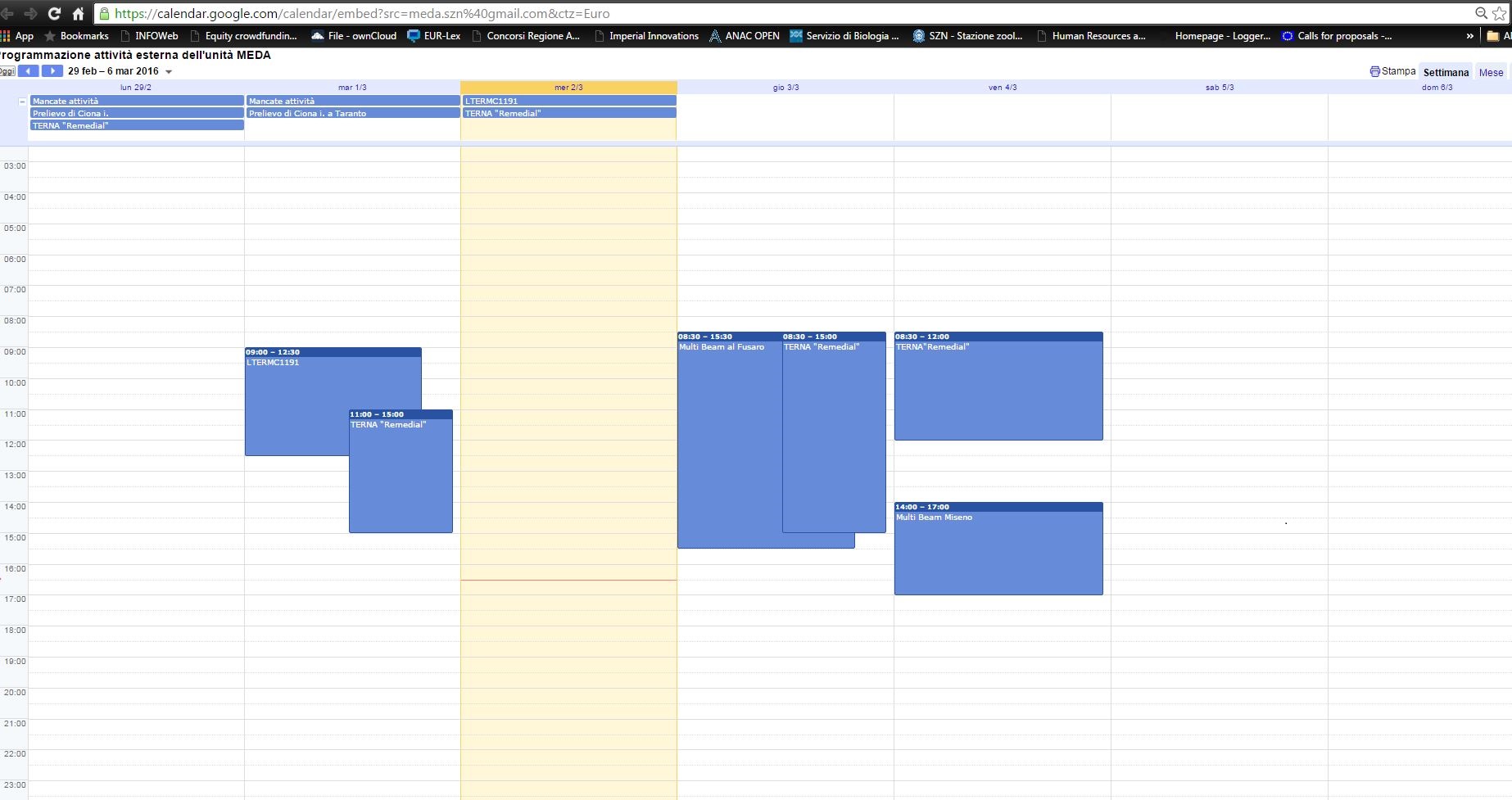

The MEDA unit manages the two coastal vessels (M/B Vettoria and M/B Hippocampus) used for environmental monitoring, research and teaching. The service includes the maintenance and calibration of the on-board instrumentation, and support for their use in research and data collection activities. In addition, the MEDA collaborates with the University of Naples, providing teaching support through exercitations on board of the M/N Vettoria. |

| Services provided |

Availability of two vessels complete of crew and equipment. Assistance in sampling, collection of biological material, and in the acquisition of instrumental data. Teaching on board the M/B Vettoria:

|

| Equipment |

M/B Vettoria

M/B Hippocampus

|

| Contacts |

Fabio Conversano Tel. + 39 081 5833357 e-mail: fabio.conversano(at)szn.it |

Monitoring and Environmental Data Unit

| Description |

Acquisition of the key hydrographic data, water sample collection and pretreatment (for the analyses of the main physical, chemical and biotic variables). These activities are mainly carried on board the M / N Vettoria or on other research vessels. Moreover, in absence of suitable support structures, a fully equipped mobile laboratory can be set up, allowing the first processing of samples. |

| Services provided |

ü Inorganic nutrients, ü Total and dissolved N and P, ü Dissolved oxygen, ü Dissolved organic carbon (DOC), ü Particulate organic carbon (POC) ü Total suspended solids (TSS), ü Chlorophyll a and Photosynthetic pigments ü Picoplankton and bacteria ( for FCM analysis) ü Plankton

|

| Equipment |

Multi-parametric CTD probes and Automatic sampler |

| Contacts |

Fabio Conversano Tel. + 39 081 5833357 e-mail: fabio.conversano(at)szn.it |

Rules for Request of Fellowships (In Italian)

Contribution of marine biology and biotechnology to the "Blue Growth"

Departments involved

"Integrative Marine Ecology" (EMI) – leader

"Biology and Evolution of Marine Organisms" (BEOM)

"Research Infrastructure for Marine Biological Resources" (RIMAR)

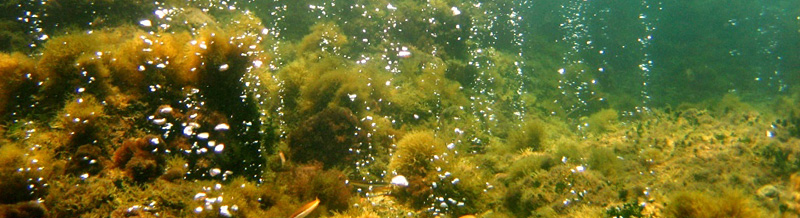

Marine biology, the discovery of new organisms and the understanding the interactions and adaptations of organisms are part of basic research of this Research Area. This represents the main focus for new discoveries, including the Biotechnological applications (i.e., the application of advanced techniques and innovative knowledge to develop biological products and other factors beneficial to humans). Blue Biotechnologies are increasingly important in Europe and at international level, and will contribute to shape the future of our economies.

Marine biotechnology is also central in the objectives of Horizon 2020.

This SZN Programme covers different research areas and is implemented through the execution of the following objectives:

Objective 1. Marine Biodiversity: ecology of marine organisms and identification of species of biotechnological interest

Objective 2. Potential of marine biotechnology in the pharmaceutical field

Objective 3. Potential biotechnology of marine organisms in the field nutraceutical, cosmetic and environmental products.