The foundation

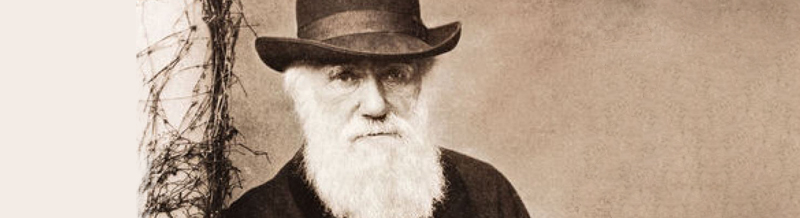

The foundations of the Zoological Station were laid in March 1872. Anton Dohrn, founder and first director, was born in Stettin, in Pomerania, now part of Poland, in 1840, into a well-to-do bourgeois family. Dohrn studied zoology and medicine at various German universities, but without much enthusiasm. His ideals changed in summer 1862 when he arrived at Jena where Ernst Haeckel introduced him to the works and theories of Charles Darwin. Dohrn became a fervent defender of Darwin's theory of 'descent with modification', the theory of evolution by natural selection. He decided to devote his life to collecting facts and ideas in support of Darwinism, the starting point of a lifelong adventure.

The foundations of the Zoological Station were laid in March 1872. Anton Dohrn, founder and first director, was born in Stettin, in Pomerania, now part of Poland, in 1840, into a well-to-do bourgeois family. Dohrn studied zoology and medicine at various German universities, but without much enthusiasm. His ideals changed in summer 1862 when he arrived at Jena where Ernst Haeckel introduced him to the works and theories of Charles Darwin. Dohrn became a fervent defender of Darwin's theory of 'descent with modification', the theory of evolution by natural selection. He decided to devote his life to collecting facts and ideas in support of Darwinism, the starting point of a lifelong adventure.

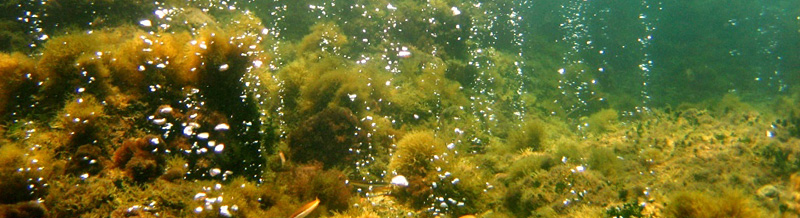

During his academic career, Dohrn worked several times at facilities located on the seashore: Helgoland, Hamburg, Millport in Scotland and Messina. Here took shape the project to cover the globe with a network of stations of biological research, similar to train stations, where scientists could stop, collect material, realize observations and experiments, before moving to the next station. The possibility to use marine organisms for studies of systematic, physiology and morphology, as well as their possible economic interest, had led many biologists and academic institutions to try to establish research facilities on the shores of the sea. The first marine laboratory was founded in 1843 in Oostende. In France, the first workshop on the shores of the Sea was founded during the 50s in Concarneau, on the southern coast of Brittany. A French laboratory was founded in Wimereux, Roscoff in 1873, and another laboratory was founded in 1881 in Banyuls-sur-Mer on the Mediterranean coast. In the United States the stages were substantially similar, indicating the existence of a widespread need for this type of institutions. Louis Agassiz in 1873 founded the Anderson School of Natural History, a Pekinese Island, Johns Hopkins University in 1878 he founded the Chesapeake Zoological Laboratory, was founded in 1888 at the Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory and in 1892 on the west coast, the Hopkins Marine Station California. All these institutions were still marine structures linked to research institutions or universities, and not independent structures that could host a variety of different researchers and projects. In addition, the American and French marine institutions were mainly for educational purposes, although during the Summer research was carried out, while the Zoological Station in Naples, as the laboratories in Trieste and Sevastopol, were used exclusively for research and advanced teaching

Facing many difficulties, Dohrn started to fantasize about the possibility for marine biologists to reach the sea and to find a work table ready, with a laboratory, services, chemicals, magazines and books, and information on where and when certain species could be found, together with information on the local conditions of the sea, the sea bed, the coast. Dohrn, after trying to carry out his project in Messina, decided that Naples would be the ideal place for his station. The choice of this city was due to the great biological richness of the Mediterranean Sea and to the opportunity to develop a research of great international importance in a city internationally oriented and large. After visiting the aquarium in Berlin, which had just been opened, he had thought that a public aquarium could earn enough to pay for a permanent assistant for the laboratories. Naples, with its 500,000 inhabitants was one of Europe's largest and most attractive city, with a large influx of tourists (30,000 per year), potential visitors of the aquarium.

Facing many difficulties, Dohrn started to fantasize about the possibility for marine biologists to reach the sea and to find a work table ready, with a laboratory, services, chemicals, magazines and books, and information on where and when certain species could be found, together with information on the local conditions of the sea, the sea bed, the coast. Dohrn, after trying to carry out his project in Messina, decided that Naples would be the ideal place for his station. The choice of this city was due to the great biological richness of the Mediterranean Sea and to the opportunity to develop a research of great international importance in a city internationally oriented and large. After visiting the aquarium in Berlin, which had just been opened, he had thought that a public aquarium could earn enough to pay for a permanent assistant for the laboratories. Naples, with its 500,000 inhabitants was one of Europe's largest and most attractive city, with a large influx of tourists (30,000 per year), potential visitors of the aquarium.

Putting together imagination, willpower, diplomatic skills and a good dose of luck, thanks to the friendly support of scientists, artists and musicians, Anton Dohrn overcame doubt, ignorance and misunderstanding and was able to persuade the local authorities to give him, free of charge, a piece of land on the shore of the sea in the beautiful Villa Comunale, called Royal Park. He promised to build the Zoological Station at his own expenses. Dohrn knew exactly what he wanted and how, and he prepared the construction projects. The foundations were laid in March 1872 and in September 1873 the building was finished. After the first building, currently the central part, a second building, connected to the first by a bridge, was added in 1885-1888, while the courtyard and the western part were built in 1905. Only fifty years later, the library was inserted between the first and the second building.

The public aquarium, which covers an area of 527 square meters, was opened on Jan. 26, 1874 and it remains unique because it has changed very little since its creation, and it is the oldest aquarium in the nineteenth century still working, exclusively dedicated to the fauna and flora of the Mediterranean. It was built under the supervision of William Alford Lloyd, a British engineer who had contributed to the project of public aquariums in Hamburg and London.

The official opening of the Zoological Station took place in April 14, 1875 and in December of that year contract was signed between Anton Dohrn and the City of Naples, represented by the Mayor, Senator Antonio Winspeare.

One feature important for the success of the institution was the remarkable agility and flexibility of its structure. It was an international institution by nature, founded by a German, managed as a family business and organized according to the German academic model, but localized in Italy, with an opening at the scientific and financial contributions of each country and institution. The idea of an agile, flexible, small but full of courage and spirit of initiative, characterizes the 'spirit' of the Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn, from its origins to today.

In order to promote the international nature of the station and to ensure its economic independence, and thus political, and the freedom of research, Dohrn introduced a series of innovative measures to finance his project, like renting work and research spaces ("research tables") for an annual fee the partners (universities, governments, scientific institutions, private foundations, even individuals) could finance a one-year-stay in Naples of a scientist, who would find what needed to carry out his research project (space in a laboratory animal, a great library and the help of a technical expert), "without conditions", meaning that the researchers were completely free to pursue their own projects and ideas.

Dohrn also began, as an additional source of revenue, to send samples and biological preparations. Thanks to the ability of another Neapolitan, Salvatore Lo Bianco, who started to work at the station at the age of 14 years. The methods of conservation of marine organisms were improved to the point that the Zoological quickly became renowned for the beauty and technical perfection of its collections of preserved marine animals. Samples and collections were sold to museums, universities, schools and individuals. Salvatore Lo Bianco also became a systematic value and many guests of the station in their publications have recognized its important contribution to research.

Convinced that the availability of a good literature was necessary for a cutting-edge research, Anton Dohrn donated his important library to the Zoological Station and requested donations to scientific publishers, academics and scientists, as Darwin, Huxley, Virchow. Overall, the bibliographic collections of the Stazione Zoologica quickly became an invaluable instrument for bibliographic research and in fact many scientists have sometimes traveled to Naples in the exclusive purpose of having access to the library, still unmatched in Europe.

The Stazione Zoologica offered its guests the best scientific displays available, acquired through donations or particularly favorable prices. Thus, the latest models of Zeiss microscopes were systematically tested and made available in Naples and Ernst Abbe, mathematician, physicist and partner of Zeiss, one of the closest friends of Dohrn, allowed the purchase of microscopes and other optical equipment with a substantial reduction. In return, the researchers of the Stazione Zoologica suggested ways to improve the tools and the made Zeiss known to the international scientific community. Microtomes, methods of cutting and coloring were also tested and improved assistants and guests of the station, thus maintaining the high technical level of the methods and tools available to researchers.